The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

Conflict is the lifeblood of story.

In real life, conflict is something we generally want to avoid. Stories, on the other hand, require conflict. This discrepancy is an indicator of the underlying purpose of stories as a kind of training ground, a place where we learn to deal with conflict without having to suffer real-life consequences.

In this post we will look at:

- An Analogy

- Archetypal conflict in stories

- Conflict between characters

- Conflict within a character

- The central conflict

Along with language (in some form or other, be it as text or as the language of a medium, such as film) and meaning (intended by the author or understood by the recipient), characters and plot form the constituent parts of story. It is impossible to create a story that does not include these four components – even if the characters are one-dimensional and the plot has no structure. However, it is formally possible to compose a story with no conflict.

It just won’t be very interesting.

(more…)

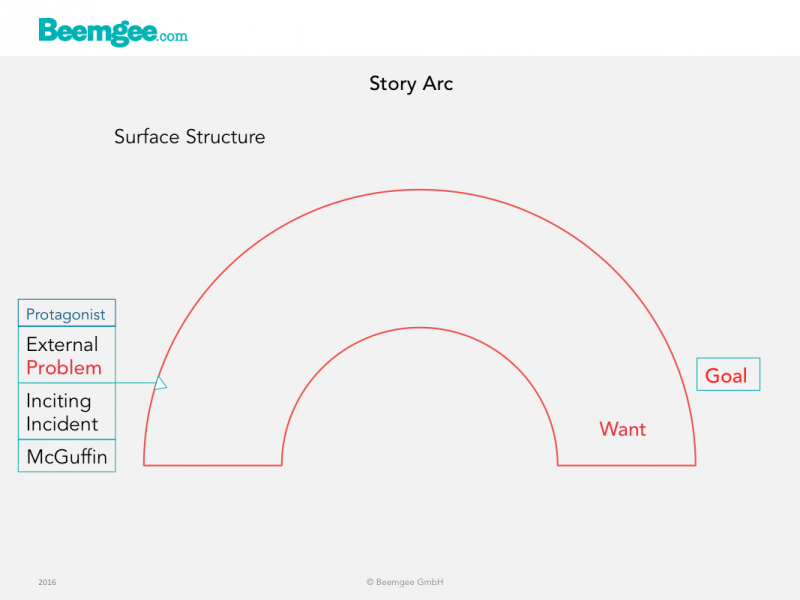

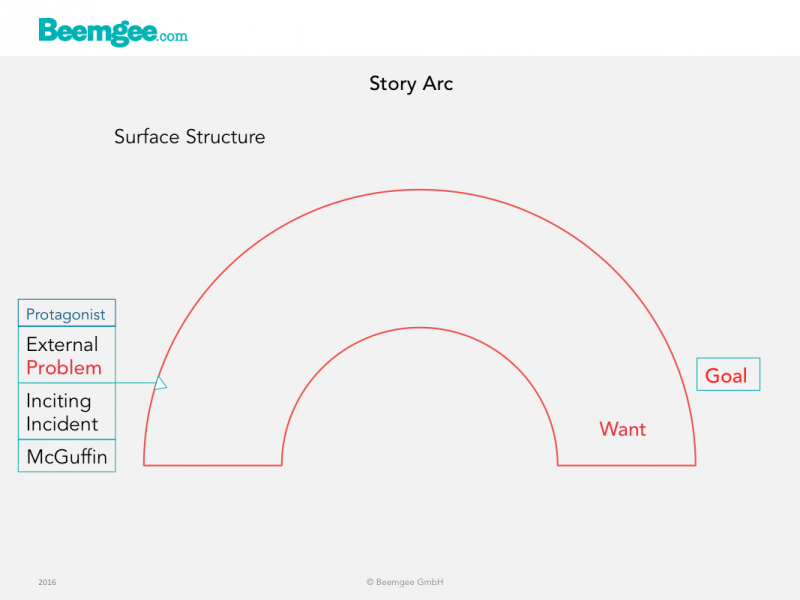

In storytelling, a McGuffin (or MacGuffin) is something that the protagonist is after – along with most other characters in the story.

The use of a McGuffin is a device the author employs in order to give a story direction and drive.

Easy to spot McGuffins are the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders Of The Lost Ark, the statuette in The Maltese Falcon, private Ryan in Saving Private Ryan, the ring (more specifically, the act of its destruction) in Lord Of The Rings. Note how in these examples, the McGuffin is in the title of the story. The McGuffin may be so deeply embedded in a story structure that it becomes what the story is about, on the surface at least.

Typical genres that have McGuffins are comedy, crime, adventure, fantasy and other quest stories. But conceivably, a dressed up McGuffin might be found in any genre.

Nor does a McGuffin have to be an object. It could be a person or a quality. In a story of several characters vying for the love of one other character, that love might be considered the McGuffin. A place might become a McGuffin too – consider the role of the planet Earth in Battlestar Galactica.

In terms of narrative structure, a McGuffin occupies the(more…)

Theme is a binding agent. It makes everything in a story stick together.

To state its theme is one way of describing what a story is about. To start finding a story’s theme, see if there is a more or less generic concept that fits, like “reform”, “racism”, “good vs. evil”. The theme of Shakespeare’s Othello is jealousy.

Once this broadest sense of theme is established, you could get a little more specific.

Since a theme is usually (though not always) consciously posited by the author, it has some elements of a unique and personal vision of what is the best way to live. At best, this is expressed through the structure of the story, for instance by having the narrative culminate in a choice the protagonist has to make. The choices represent versions of what might be considered ways to live, or what is “right”.

But beware! This is a potential writer trap. See below.

How story expresses theme

Theme is expressed, essentially, through the audience’s reaction to how the characters grow. A consciously chosen theme seeks to convey a proposition that has the potential to be universally valid. Usually – and this is interesting in its evolutionary ramifications – the theme conveys a sense of the way a group or society can live together successfully.(more…)

It’s the way you tell it

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story. The difficulty is that story, like truth, is an illusion created by narrative.

What does that mean?

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of narrated events; events consist of actions carried out by characters; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. We are pinpointing the use of the term for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. These tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)