Awareness and Revelation

What’s the problem? Does the character know?

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

- A character’s awareness of his or her own internal problem or motivation

- A difference between one character’s knowledge of what’s going on and another’s

- The narrator knows more about what is going on than the character

- The audience/reader knows more than the character – dramatic irony

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

- Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

- The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

- Surface Structure and Deep Structure

- The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

In many stories, major characters, especially the protagonist, have some sort of character flaw that holds them back from achieving what they want or that causes them to hurt other characters around them. Quite often, the characters are not aware of this failing until later in the narrative, when the story leads them to a sort of insight or revelation. This moment of self-discovery allows them to change their typical actions in order to make good their failing. In short, to grow into a better person.

Such a self-revelation can by definition only come about if the character is unaware of the internal problem at the beginning of the story. Conflict makes stories interesting, and it is the conflict between how the character sees him or herself and how the rest of the world – or the audience/reader – sees him or her that can make the character interesting. When will this character realise the truth?

There is a tricky writer trap here, but we’ll get to that later.

Furthermore, the revelation should not be confused with a reveal, which is a scene type. In a reveal, the audience learns something it previously did not know. A reveal usually marks a plot twist, a “the plot thickens” moment.

Despite the pitfalls involved, revelation is perhaps the single most powerful element of storytelling. That is one of the reasons why mystery and crime fiction is so popular – because these genres inherently feature a revelation when the mystery is solved.

Without revelation, there can be no realisation, and therefore no learning experience, which is at heart what stories are all about. Not only for the protagonist, but for the recipient – the reader or viewer. A good story will often have a single pinpointable moment where the recipient, or at least the protagonist, realises something important. This scene can give meaning to the entire story.

Some examples: The audiences fully realises the depth of Michael Corleone’s fall at the moment the door is closed to his wife. Indiana Jones realises that spirituality is not all hocus pocus and mumbo jumbo as angels and demons appear when the Lost Ark is opened.

The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

The bulk of the narrative can be described as the story journey, beginning from the point at which the character acts on the external problem and moving all the way to the denouement. In the story journey, awareness of the internal problem often arises at the midpoint, though at first it may be ignored or denied. Proper awareness and the final choice of how to act upon it typically comes at the crisis point of confrontation towards the end of the narrative.

So awareness may not come in one go, but might grow, especially in the second half of the narrative. Essentially, the story journey consists of the character either taking action or discovering information, and of course the latter especially leads to growing awareness.

Awareness of the inner problem comes to a character by revelation, typically at the midpoint and/or at the crisis.

Awareness of the inner problem comes to a character by revelation, typically at the midpoint and/or at the crisis.

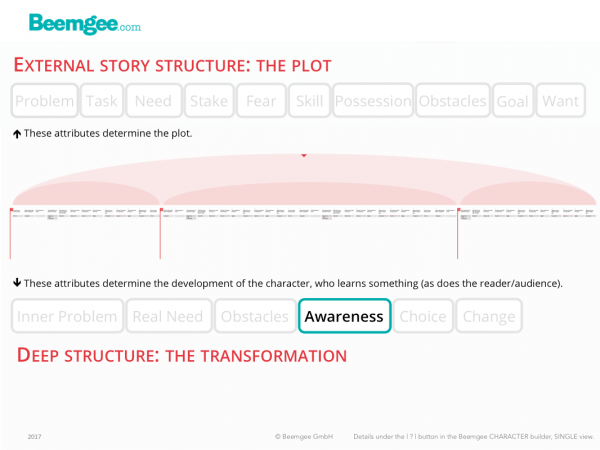

Surface Structure and Deep Structure

We have said that the external problem forms the basis of the plot, and is therefore superficially what the story is about. The internal problem leads to character growth – which is good, because it gives the story a deeper level of meaning.

What does deeper level of meaning mean?

By getting the audience/reader to watch a character deal with an internal problem, the author can impart a universal truth about human emotions and how people act towards each other. On the whole, this is good. It’s what stories are for.

But for an author there is a danger not only of overdoing it, of moralising. There is also the other danger: feeling one has to do it at all. That’s the writer trap of revelation.

The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

It would be excessive to suggest that the audience/reader expects or demands a self-revelatory insight of the protagonist in the story. Or at least we would say that the audience/reader should not necessarily expect this sort of effect. After all, why must the protagonist realise that s/he was wrong to //insert character flaw//?

Antagonists are often be unyielding. But it can be just as powerful, perhaps even more so, when an author defies convention and lets the protagonist keep and savour the flaw too. An unflinching protagonist who is aware of and steadfastly holds on to his or her failings and shortcomings can be more interesting than one who “learns” and is made “better” in the eyes of society. For society, read audience. We’ll posit as examples to consider stories such as Dirty Harry or American Psycho. Do those protagonists learn by revelation of their internal problem? Or do we find them fascinating because they don’t? Indeed, do these characters perhaps force us to consider our own internal problems?

It’s up to the author to decide what story to tell, and how to tell it. Many workshops and modern books on storytelling suggest that the protagonist requires self-revelation, i.e. revelation of the internal problem (though they might put it differently). While this is undoubtedly a valid and effective technique, we would point out that alternatives are perfectly valid too.

There is no absolute blueprint for stories.

Nonetheless, one of the deepest and most essential elements of story is revelation. More important still than that the protagonist experiences revelation is that the audience does. This emotion – the aha-effect, if you like – is one of the most satisfying for readers or viewers.