Reflections on dialectically guided writing, or: Can dialectics help us tell better stories?

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Prof. Dr. phil. Richard Sorg, born in 1940, is an expert in dialectics. What is that, and what does it have to do with my novel? Well, “All great, moving and convincing stories are inconceivable without the central significance of the contradictions and conflicts that represent the driving energy of movement and development.” This puts us in the middle of dialectics. And of storytelling.

After studying theology, sociology, political science and philosophy in Tübingen, West Berlin, Zurich and Marburg, Richard Sorg taught sociology in Wiesbaden and Hamburg. His book “Dialectical Thinking” was recently published by PapyRossa Verlag. (Photo: Torsten Kollmer)

Ideas that contain a potential for conflict.

Sometimes there is a single but central chord at the beginning of a piece of music, even an entire opera, which is then gradually unfolded. Its inherent aspects, harmonies and dissonances emerge from the chosen, sometimes inconspicuous beginning, undergoing a dramatic, conflictual development, so that a whole, complex story emerges at the end of the path of this simple chord after its unfolding. This is the case, for example, with the so-called Tristan chord at the beginning of Richard Wagner’s opera “Tristan und Isolde”, a leitmotif chord that ends with an irritating dissonance.

The beginning of a story is sometimes an idea, an idea which you may not know how to develop. But some such ideas or beginnings carry a potential within them that is capable of unfolding and which holds unimagined development possibilities. ‘Candidates’ for viable beginnings – comparable to the dissonant Tristan chord mentioned above – are those that contain a potential for conflict or contradiction within. But it can also be a calm with which the matter is opened up, a calm that may then prove to be deceptive. We also find something similar in some dramas, for example with Bertolt Brecht.

And with that, we are already in the middle of dialectics. (more…)

“Where’s the story set?”

The answer provides many clues about the story in question. While we ask “where”, the setting actually encompasses somewhat more than location. Let’s find out how setting relates to

- time

- genre

- story world

- premise

Time

Each Star Wars story reminds us of the setting before it even starts: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”. In being reminiscent of “once upon a time”, the famous opening establishes that this is essentially a fairy tale with spaceships.

“Middle-earth” is a valid answer to the question above for The Lord of the Rings. One might be tempted to explain that this is a fictitious realm, maybe say something about how its technology relates to the actual Earth’s history, and possibly mention the connection to the Midgard of Norse mythology.

So in addition to describing physical space, both these examples contain hints and associations about the time when the events of the story take place. (more…)

The process of writing is unique to each author.

There is no right or wrong way to write a work of fiction. Perhaps the main thing is to just sit down and get on with it.

Many authors start by writing the beginning of the story and working their way through to the end. This seems intuitive, as it mirrors the way narratives are normally received – from opening to resolution. Furthermore, it allows a development of the material that feels natural, beginning probably with a setting and a character or two and growing in complexity as the story progresses.

But this isn’t the only way to get a story written. The author is not the recipient, after all. The author is the creator.

Creative habits seem to differ according to medium. Most screenwriters spend a lot of time working out the intricacies of plot and complexities of character before beginning to actually write the screenplay. Some novelists, on the other hand, seem to require the writing process in order to get to grips with the material. For such authors, the act of working on text is so intimately intertwined with the craft of dramaturgy that the shaping of the story has to be performed simultaneously with the writing of it.

Flow

In some cases, a writer might have a fairly clear idea in mind where the story is headed, or already be aware of certain key scenes that ought to be included. In others, the author may not know how the story ends(more…)

The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

Conflict is the lifeblood of story.

In real life, conflict is something we generally want to avoid. Stories, on the other hand, require conflict. This discrepancy is an indicator of the underlying purpose of stories as a kind of training ground, a place where we learn to deal with conflict without having to suffer real-life consequences.

In this post we will look at:

- An Analogy

- Archetypal conflict in stories

- Conflict between characters

- Conflict within a character

- The central conflict

Along with language (in some form or other, be it as text or as the language of a medium, such as film) and meaning (intended by the author or understood by the recipient), characters and plot form the constituent parts of story. It is impossible to create a story that does not include these four components – even if the characters are one-dimensional and the plot has no structure. However, it is formally possible to compose a story with no conflict.

It just won’t be very interesting.

(more…)

The step outline is the scene by scene (step by step) account of what happens in the story.

Like a textual storyboard, the step outline presents the narrative in its entirety – without actually being the narrative. It is a complete report in that it describes every plot event.

Cause and Effect

The step outline therefore makes one of the most important principles of storytelling very clear, cause and effect.

Apart from the kick-off event and the closing event, every plot event fulfils two functions, at least to an extent:

- It is a precondition of events that follow it in the narrative

- It is an inevitable consequence of events that have preceded it in the narrative

The step outline should make it easier to understand how the individual events relate to each other in this chain of cause and effect. The step outline may thus be read as the author’s construction plan of the narrative.(more…)

Detectives and other investigators abound on our TV and cinema screens.

In the western world, crime fiction – mystery, thrillers, suspense, etc. – makes up somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of all fiction book sales. Why is the crime genre so popular?

Crime is fascinating, to be sure, because most of us don’t commit it. But the popularity of the genre has little to do with crime per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of how storytelling works.

In this article we will be looking at:

- Cause and Effect

- Agency

- The Narrative Principle

- Why Some People Don’t Like Crime Stories

- The Search For Truth

- How Crime Is Like Comedy

Crime fiction exhibits most clearly one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In crime fiction,(more…)

The protagonist is the main character or hero of the story.

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. And for simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

- Is the protagonist the most interesting character in the story?

- What are the most important aspects of the protagonist for the author to convey?

- What about the transformation or learning curve?

How interesting must the protagonist be?

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

(more…)

Events propel narrative. Narrative consists of a chain of events.

These do not have to be spectacular action events – they can be internal psychological events if your story is about a man who does not leave his room, or spiritual events if you are recounting the story of Buddha sitting beneath the tree. But events there must be if there is to be a story.

In this post we’ll discuss –

Events in a story are effectively bits of knowledge the author wants to impart – in a particular order, the narrative – to the recipient, i.e. the reader or audience. The story is told when all the pertinent knowledge has been presented, when all the bits of information necessary for the story to feel like a coherent unity are conveyed. An author(more…)

Any event happens sometime and somewhere.

We have discussed time a great deal in this blog. Of course, the spatial dimension may be just as relevant.

The Story World

We may distinguish between the overall story world location and specific locations. By story world we mean the entire setting and logical framework of the story. This is always unique to the story, although that becomes most obvious in stories set either in a fantasy world (like The Lord Of The Rings) or in stories that have a setting tightly bound to a geographical feature, such as Heart of Darkness, Apocalypse Now, or Deliverance. In each of these latter examples, a river – and the journey up or down it – provides the story world. Yet story world is more than just physical location. It describes an entire environment, including the ethical dimensions. Consider Wall Street or The Big Short, stories that describe “worlds” where making money comes first.

The setting is usually established in the first part of the story, and the rest of the story should be true to what has been set up at the beginning.

Locations

Within the entire “world” come the specific locations(more…)

Well, ideally, a story is as long as it needs to be, and no longer.

There are norms that have developed over time, and which are more or less inculcated into us due to our exposure to stories in their typical media. For example, a typical feature length film of roughly two hours has between forty and sixty scenes. Formatted according to industry standards, a screenplay has approximately as many pages as the finished movie would have minutes. In terms of plot events, some people in Hollywood believe that a commercial movie should have exactly forty (which in Beemgee’s plot outlining tool would mean exactly 40 event cards).

Content and form may be mutually determined, to some degree at least. A short story is usually considered such if it has less than 10.000 words. By dint of its length, a short story probably concentrates on one character’s dealing with one specific issue or occurrence, and is unlikely to have subplots or multiplots (that is, be about more than one protagonist).

(more…)

Dialog enlivens stories. But writing dialog well is really hard.

For a start, there is the rule of thumb that it’s better for the author to use action to explain things or move the plot forward than dialog. When the author makes characters say things solely to convey some bit of knowledge to the audience or reader, the lines tend to feel false.

Nonetheless, Elmore Leonard noted how readers don’t usually skip dialog. People like dialog. Dialog can be exciting. So authors had better not avoid it altogether either.

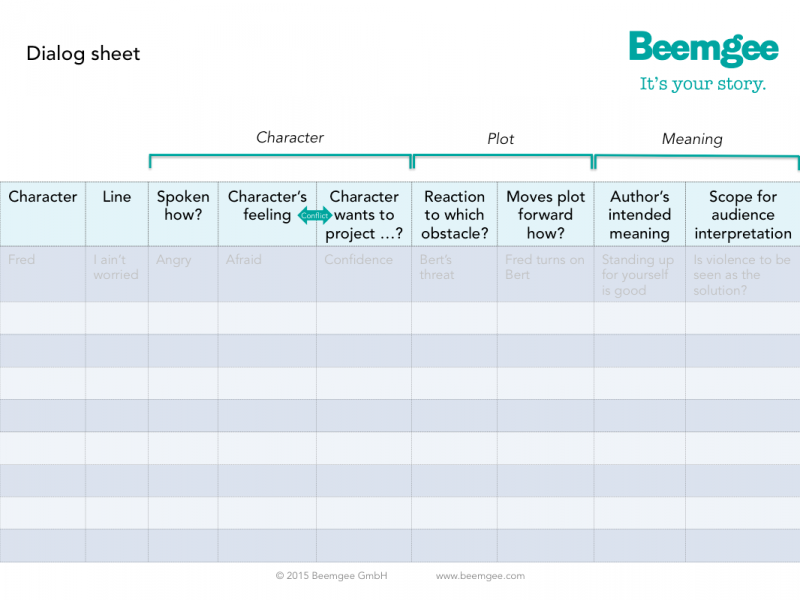

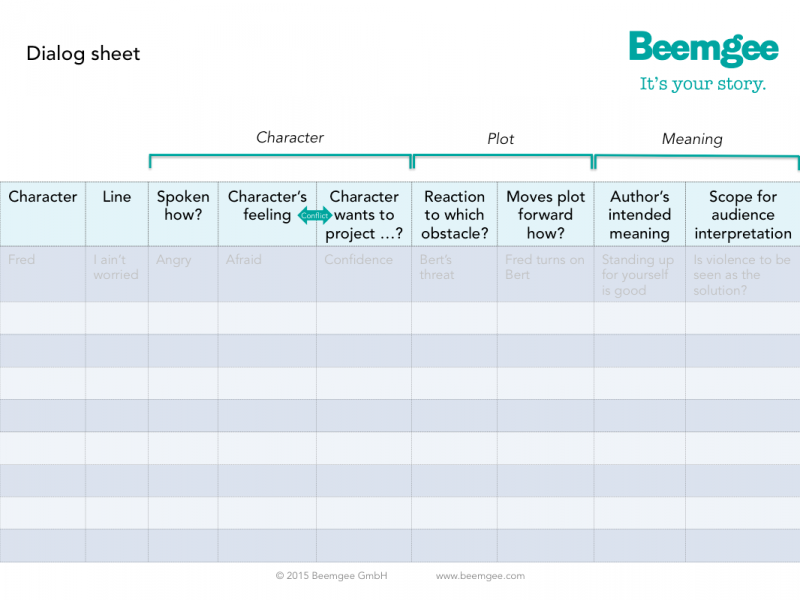

As an author, here are the seven things you ought to consider about every single line of dialog you put into your characters’ mouths. We’ve created this free table to help you. Feel free to download, use and share it.

1

If you’re writing(more…)

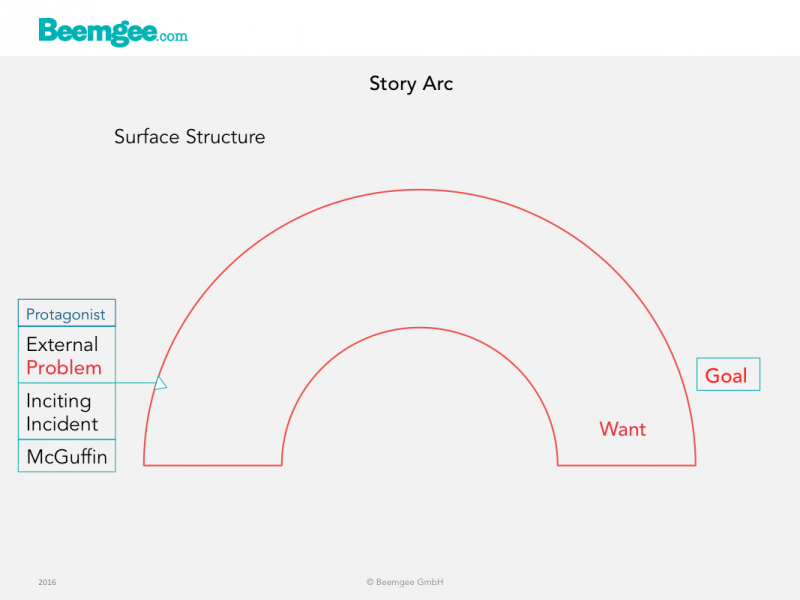

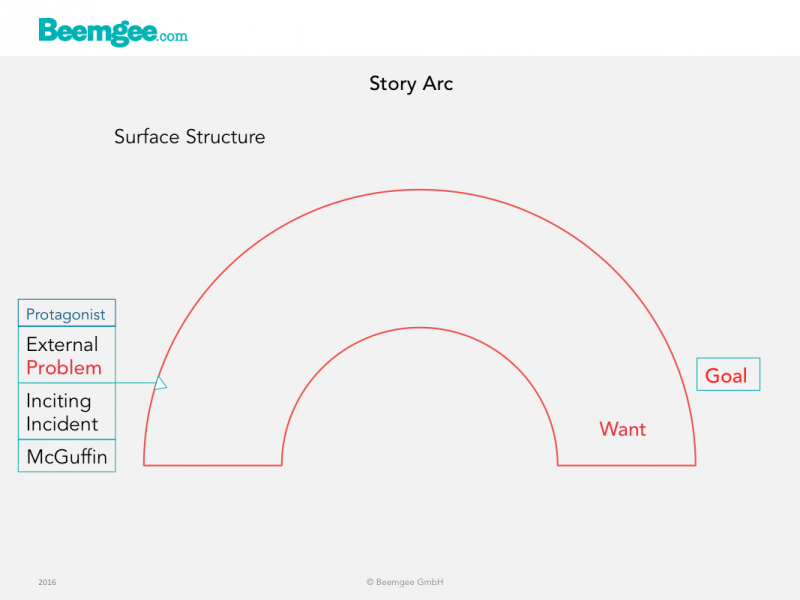

In storytelling, a McGuffin (or MacGuffin) is something that the protagonist is after – along with most other characters in the story.

The use of a McGuffin is a device the author employs in order to give a story direction and drive.

Easy to spot McGuffins are the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders Of The Lost Ark, the statuette in The Maltese Falcon, private Ryan in Saving Private Ryan, the ring (more specifically, the act of its destruction) in Lord Of The Rings. Note how in these examples, the McGuffin is in the title of the story. The McGuffin may be so deeply embedded in a story structure that it becomes what the story is about, on the surface at least.

Typical genres that have McGuffins are comedy, crime, adventure, fantasy and other quest stories. But conceivably, a dressed up McGuffin might be found in any genre.

Nor does a McGuffin have to be an object. It could be a person or a quality. In a story of several characters vying for the love of one other character, that love might be considered the McGuffin. A place might become a McGuffin too – consider the role of the planet Earth in Battlestar Galactica.

In terms of narrative structure, a McGuffin occupies the(more…)

In storytelling, one of the most far-reaching decisions an author must make is how to narrate the story. Or: Who will be the narrator?

While not a traditional archetype, and in many cases not even a participating character, the narrator is never really quite the same entity as the author either. Standard narrator types are:

- first-person, where usually the protagonist tells his or her own story

- third-person limited, where a narrator tells a story from one character’s point of view only, meaning that the audience/reader is not told of any events that this character is unaware of

- third-person omniscient, where the narrator can relate what any of the characters are doing and thinking, and is not limited in what to present to the audience/reader

In film, first person and third-person limited effectively amount to the same thing: the audience gets only one person’s perspective on the story (there is also the first-person camera angle, but rarely is an entire film presented that way). In prose, first and third person is the difference between “I did this” and “she (or he) did that”. This is a stylistic choice. In the sense of what the narrator knows and tells, there is not necessarily much difference.

But potentially there is. A narrator who (more…)

Theme is a binding agent. It makes everything in a story stick together.

To state its theme is one way of describing what a story is about. To start finding a story’s theme, see if there is a more or less generic concept that fits, like “reform”, “racism”, “good vs. evil”. The theme of Shakespeare’s Othello is jealousy.

Once this broadest sense of theme is established, you could get a little more specific.

Since a theme is usually (though not always) consciously posited by the author, it has some elements of a unique and personal vision of what is the best way to live. At best, this is expressed through the structure of the story, for instance by having the narrative culminate in a choice the protagonist has to make. The choices represent versions of what might be considered ways to live, or what is “right”.

But beware! This is a potential writer trap. See below.

How story expresses theme

Theme is expressed, essentially, through the audience’s reaction to how the characters grow. A consciously chosen theme seeks to convey a proposition that has the potential to be universally valid. Usually – and this is interesting in its evolutionary ramifications – the theme conveys a sense of the way a group or society can live together successfully.(more…)

One of the most important choices an author must make concerns Point of View.

In storytelling, people use the term Point of View (or PoV) to refer to different things. We’ve narrowed it down to four definitions:

- The overall perspective from which a story is told

- The scene by scene perspective of a story

- The narrator’s point of view

- Attitude or belief of the author

Overall perspective

The entire Star Wars saga is, in very general terms, told from the point of view of the two characters that have least status: the robots C-3PO and R2-D2. They are not present in every single scene, but they are part of the overall course of events – and in a ironic tip of the hat to their function of providers of overall point of view, George Lucas has C-3PO relate the entire story so far to the Ewoks in Return of the Jedi.

George Lucas borrowed the idea from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, which tells a story of generals and princesses from the point of view of two peasants. These two are involved in the action, but understand less about what they see going on than the audience does.(more…)

It’s the way you tell it

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story. The difficulty is that story, like truth, is an illusion created by narrative.

What does that mean?

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of narrated events; events consist of actions carried out by characters; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. We are pinpointing the use of the term for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. These tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)

Narrative is made of successive events.

Narrative is the order in which the author presents the story’s events to the recipient, i.e. the audience or reader. Chronology is the order of these events consecutively in time. Some people use terms from Russian Formalism, Syuzhet and Fabula, to make the distinction.

While the convention is linear, i.e. to relate the story’s events consecutively in time, that is chronologically, we are also very used to narratives which move certain events around. An event may be moved forward, meaning towards the beginning of the narrative, perhaps even to be used as a kick-off. Or possibly events may be withheld from the audience or reader and pushed towards the end, perhaps to create a revelation late in the narrative for a surprise effect – though this technique often feels cheap. Also, an author may use flashbacks to insert backstory events from the past, the past being all relevant events that are prior to the events in the narrative.

As authors, when we begin composing a story, we(more…)

How aware are you of the creative process while writing?

Do you really consciously control what comes out of your fingers onto the page?

Even when writing happens “naturally”, while the words are pouring forth, the author is probably already performing a first level check that precedes the more detached and critical control of rewriting. If you want to make yourself more conscious of this process, consider putting an imaginary parrot on your shoulder every time you sit down to write.

A parrot?

Well, the creature of your choice. At Beemgee, it’s a parrot.

The parrot reads what you write as you write it and squawks a running commentary into your ear. It might commend a good sentence or it might censure. It might suggest alternative words or phrases. It may like or hate a paragraph.

The parrot has three main hobbyhorses: relevance, surprise, and recognition.

Relevance – (more…)

Some people say they don’t like plot.

For some people, plot is like a dirty word. They prefer their stories to concentrate on character. Or premise. Or language. It is action movies or thrillers by Michael Crichton or Robert Ludlum that have plots.

At Beemgee, we believe that the four pillars that hold a story up are plot, character, premise, and language – with conflict as girders. Every story, no matter how “good” or “bad”, exhibits all four of these pillars. No story can really go without any one of them.

We have not found a single work of fiction in any medium or genre that does not have a plot. Ulysses has a plot. The Sound And The Fury has a plot. Even the most famous attempt in literary history to shun plot, Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne, did not manage to avoid describing events and characters. Its language is beautiful and its premise, of course, is the attempt to shun plot.

There is an intimate relationship(more…)

We humans have a built-in predisposition to expect agency.

We look for the person or thing responsible for any action or phenomena we experience; we seek to ascribe “agency” to what we perceive. What this means is that when we notice that something happened, we tend to look for the cause of the event. This probably has a simple evolutionary explanation. If we hear a rustle in the bush behind us, we immediately turn around to see what moved. This reflex is a safety mechanism to detect threats. Before homo sapiens lived in houses, the individuals for whom this reflex worked most efficiently probably lived longer, and thus had better chances of passing on their genes. The point is, we assume that something or someone caused the phenomenon (the rustle) and seek to attribute it to an agent. If we are sitting in our living room and hear a floorboard creak in the hall, we would want to know what caused it too.

This safety mechanism has all sorts of ramifications. It influences(more…)

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Guest post by Richard Sorg.