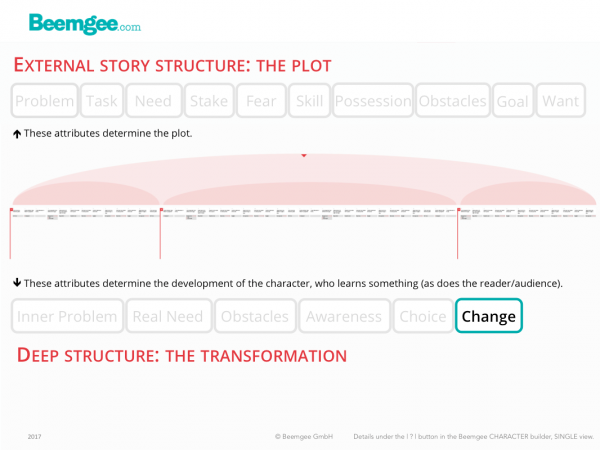

Change

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning. But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

So within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

Why?

So that the audience or reader changes also.

At least, that’s the general idea. The story provides a physical, emotional and intellectual experience – physical when your heart beats faster or your palms sweat, emotional when you feel for the characters, and perhaps intellectual too. If the story achieves none of these responses, then it has failed. An experience, again pretty much by definition, changes you. We learn through experience; so if you have changed, chances are that you have learnt something.

So it is not only within the story that a change takes place. It takes place outside of the story as well, in the recipient. In some stories one may argue that no real change occurs – Alice does not obviously change due to her experience in Wonderland. But the reader has been taken on a wild journey, and the experience is likely to have left some sort of mark.

The effect change has really only occurs when the story works. For works, read “provides an experience”. How does a story do that?

By allowing the recipient, the audience or reader, to understand and feel the change within the story. That usually works by simple juxtaposition of “before and after”. Stories have a tendency to symmetry: The beginning of the story makes clear what the state is before the story journey commences, and the end of the story has a corresponding scene or event that shows what the state is after.

There is a paradox here. The change that occurs is also an expression of new equilibrium. At a very basic level, story structure can be described as follows: an external problem disturbs the equilibrium or balance of a world, the disturbance is explored, understood and dealt with, creating a new equilibrium.

1 – The protagonist changes

We have said before that a protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. We have seen that this has something to do with the want, which – whether the character achieves it or not – is usually only attainable by causing a change. Often the change involves the character’s solving the internal problem, so the change takes place within the character. This involves the recognition of the necessity for change, i.e. the acceptance of the real need, and the struggle to achieve it. So all the incidents and events in the plot, the hindrances and obstacles the characters deal with, are in themselves not so very interesting. What interests the audience or readers tends to be how these events and obstacles change the character.

Nonetheless, a story may show no more change than the solving of the external problem, which also necessitates some sort of change of the state of affairs. And that is fair enough.

2 – Several characters change

In many stories, subplots will tell of the characters that surround the protagonist, and their changes may well cast light on various aspects of the story’s theme. Or perhaps the story is an ensemble piece, where it is not easy (or even necessary) to identify a single protagonist. Or it is a romance, or buddy-story, which apparently has two main characters. Whichever – some level of change usually occurs in all the main characters.

There is one often neglected archetype who also typically changes. We call this role the contrastor. The contrastor mirrors and contrasts the protagonist, like Han Solo to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or the mother to the boy in Boyhood.

3 – The whole world changes

Quite possibly, the entire story-world may be different by the end of the story than it was at the beginning. Story-world as a concept refers to the scope of the world presented in the story, so if the field of action of the characters is small, the story-world is small too. If the story is an epic, the story-world will be big, a version of an entire world.

As an aside on this last point, consider the classical genres. Epics – again, almost by definition – describe a change in a whole world. In a way, so does tragedy, for at the end of the tragedy the world will have lost one or more of its population, since tragedy deals with the change from life to death.

Only comedy does not seek to describe a fundamental change in the story-world, and is content to merely change its inhabitants. The typical structure of comedy, whether we are talking about Aristophanes or modern TV sitcoms, has a stable situation at the beginning which is disturbed by some event or problem. The disturbance causes first a lot of messy but generally non-life-threatening chaos which is resolved by a return to the original undisturbed situation. Even if the main characters end up married, the story-world is brought back to its stable state.

So the very serious point of comedy is to demonstrate a fundamental truth: the cyclical nature of the universe. Spring always returns, no matter how bleak the winter. Day always comes, no matter how dark the night.

Change does not have to be final. Change can be cyclical. Change is life.

Read here how change is important for every single scene, though we prefer to call them plot events.