Stake

You’re on a boat, and you see somebody fall into the water. Which of the following two cases would cause you to react with stronger emotion?

- The water is four feet deep and you know that the guy who fell in is a good swimmer

- The water is four feet deep and the person who fell in is a three year old girl who can’t swim

Presumably your emotional reaction would be stronger if the child fell off the boat. Because you know that the child’s life is at stake. The first situation is not life-threatening, the only thing at stake is the dryness of the man’s clothes and his self-esteem.

The degree you care about events that happen to people, and to yourself, is directly related to what’s at stake. This applies as much to fictional characters as in the real world.

Hence it is immensely important for storytellers to impart to their audience or readers how threatening the problems are that the characters face. The audience or reader must know what is at stake for the character. What have they got to lose? Their life? Their soul? Their mobile phone?

The risk to life and limb may be apparent from the beginning, when the problems are set up. Alternatively, the scale of the threat may increase or become more specific as the story progresses. When the threat is immediate – rather than heralded for the future – the audience or reader is more likely to respond emotionally.

What must not happen is that the level of risk, threat or danger decreases as the story goes on. What’s at stake is about the turn of the screw: at first the pain is not so great, but with each stage of the story journey the pain grows more intense. For the character, and with that for the audience or reader.

That’s why in many stories the family of the protagonist is dragged into danger, usually by a nasty antagonist. The protagonist has already risked his or her life, so how does the author increase what is at stake? Threaten the spouse or child. Then what is at stake may be greater than life because, of course, a hero loves his or her family more than life itself.

Often the stakes are basic. Certain issues recur in stories because they have resonating effects within us as a species, such as survival (the necessity of food or shelter, threats to life), procreation (the omniscience of sex), or community (protecting the clan, family or home). However, what’s at stake does not have to be as universal as life and death. It is possible for an author to set up a stake and load it with meaning in the context of the story. So the stake can be something very specific to a particular character. If, say, it becomes clear early in the story that the character lives in fear of losing his or her good reputation, then that can be the stake. In Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, for example, Torvald’s action hinges on his perceived need to maintain his reputation. It might not be something the audience or reader worries about too much for him or herself, but it helps them to understand the character’s motivation if the author has established a character-specific stake. In other words, the stake does not have to be physical life or death, but may mean the equivalent of emotional or spiritual death; the person, thing or quality a character has invested the meaningfulness of his or her life into might be at stake. In Torvald’s case, the choice of investment is also his internal problem.

If a character has a prized possession, such as Linus’ security blanket, then losing it could be at stake. Indeed, a McGuffin can have this function; it is something valuable the protagonist attains, and its loss could be the stake, for example the Bodyguard’s ward.

A character does not even necessarily have to be aware of what is at stake. But the audience or reader must know. Otherwise, why should they care?

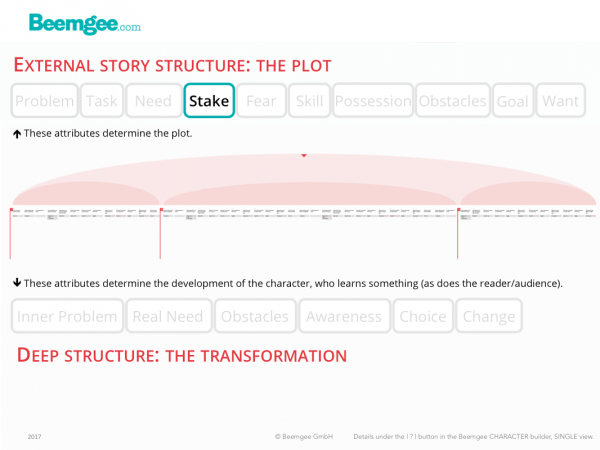

The stake is what the character has to lose, what is at risk in case of failure, and must be communicated to the audience in order to arouse empathy.