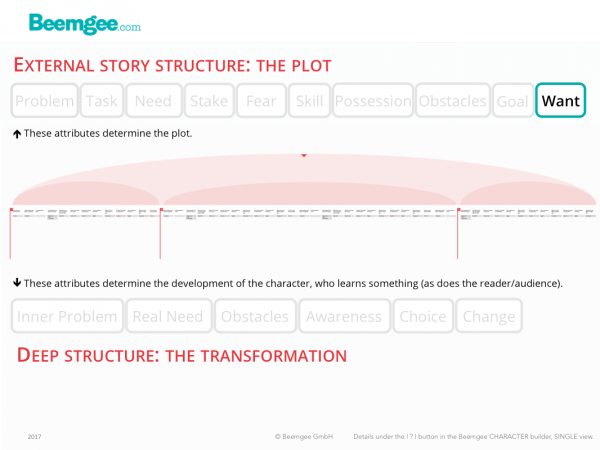

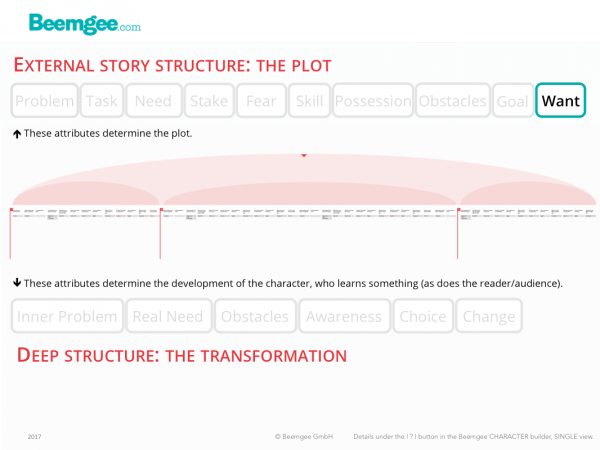

Stories are about people who want something.

We can distinguish between two different types of want:

- the wish, or character want

- the plot want

Marty McFly wishes to be a musician (character want). He also wants to get Back to the Future (plot want).

The wish or character want is a device which adds cohesion to the story, usually in the form of the set-up/pay-off. Marty is seen at the beginning of the film practicing the guitar; at the end of the film he plays at a concert. The wish is a useful technique to make the character clearer to the audience, but it is not essential to composing a story.

More important is what we have called the plot want. As a result of the external problem – the trigger event that sparks the chain of cause and effect which the bulk of the plot consists of –, the character feels an urge, which provides the motivation for the character’s actions in the story.

The want is the state after which the character strives, and is distinct from the goal.

In this post we’ll be talking about active vs. passive characters, motivation, the difference between a want and a goal, a couple of writer traps to avoid, and contradictory wants.

Active Characters

Characters have to be actively acting of their own volition. The want has to be urgent and strong enough for them to do things. If the want is missing or too weak, the character will lack motivation and appear passive. A passive character is usually not interesting enough to hold the audience’ or readers’ attention.

Why is this so?

An evolutionary explanation of stories as practice for problem-solving attempts to shed light on the phenomenon: When characters react to events rather than cause them, they appear weak, like victims. Which means that there is not much we can learn from them. Humans experience stories physically and emotionally (our hearts beat faster, our palms sweat), and since we learn from experience, we instinctively prefer stories which provide us with experiences that benefit us in some way. Which tends to be the case when we experience stories of self-motivated problem-solving.

Motivation

There is a good reason for that cliché about actors always asking about their motivation. It is motivation that prompts the characters in a story to do the things they do. Stories seem to work best not only when characters are active rather than passive, but often when they have comprehensible reasons for their activity.

The reason for what a character wants is usually comprehensible for the audience or reader because of the external problem. In simple terms, the character wants to solve the problem. Take the Cinderella story as an example. Her problem is that she is bound to the stepmother and her two nasty daughters.

In other words, the want is a vision the character has of his or her situation without the problem. Hence what the character wants is actually a particular state of being. Such a state might mean being in a position of wealth, power or respect, or being in a happily ever after relationship. Cinderella wants merely to be free of her involuntary servitude, if only for a little while.

This makes the want distinct from the goal, which is the specific gateway to the wanted state of being, as perceived by the character. A story usually sets up a goal the character needs to reach or attain in order to achieve the want. In Cinderella’s case, it is attending the ball.

So, a story has its characters pursue their wants. These different wants oppose each other, causing conflicts of interest. The conflicting wants make the characters active, and the audience/readers like stories about actions, that is, about characters who do things.

Sounds simple.

And yet frequently stories seem to mess up on this vital point.

Next to passive characters without a strong enough want, lack of clear motivation is a huge writer trap. It is possible to write a whole story full of characters who are reactive instead of active, or who do things of their own volition but without that volition being clearly recognisable to the audience/reader. It is perhaps even tempting to write stories like that, because they seem more lifelike. In real life, people do not necessarily have distinct goals. Often, our wants are vague and not clearly definable. What about writing a realistic story about a character with a general sense of dissatisfaction, who, like so many of us, has lost sight of any clear objective in life?

It’s doable, certainly. But the audience/readers will probably start to look for the specific want of such a character. They would probably begin to expect the story to be about this character’s search for a clear objective in life. That might be the want the audience would tacitly ascribe to the character.

And if the story does not bear such motivation out, the risk is significant. Because stories in which the audience does not understand what the characters want lack emotional impact.

Contradictory Wants

A way of adding psychological depth and emotional complexity to characters is to give them several and even contradictory wants. Gollum in Lord Of The Rings wants the ring. Yet a part of him also wants to give up the ring and help Frodo. Next to solving the case, Marty Hart in True Detective wants to be a good husband and family man, but he also wants affairs with other women. That’s three wants for one character.

Is it really always necessary for every character to have a clearly defined want?

No. Because, of course, there are exceptions. In certain cases, the author might deliberately obfuscate the why of a character’s actions in order to inject mystery. Not knowing something keeps the audience/reader guessing and turning the pages or not switching the channel. Usually this mystery is cleared up at some point. The audience tends to expect that. Which implies that even if the want was not made clear to the audience early in the story, it was there in the character nonetheless – and certainly the author was aware of it.

Injecting mystery in this way is not in itself a writer trap. But nearly. When tempted to use such a device, an author should at least consider if it would not actually be more interesting for the audience to know the character’s motivation.

Having said that, there are rare cases where a character’s motivation does remain unexplained. And those cases can be powerful. Especially when it’s a baddy we don’t understand.

Think of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who is simply bad to the bone and we’ll never really know what made him so. Shakespeare – deliberately, one presumes – gives no hint as to what Iago hopes to achieve by ruining Othello. Shakespeare might easily have given Iago some clearly understandable motivation, such as revenge of a past wrong, envy of Othello’s success, desire to usurp Othello’s position, lust for Desdemona. But he didn’t. And Iago is one of the most superb villains ever.

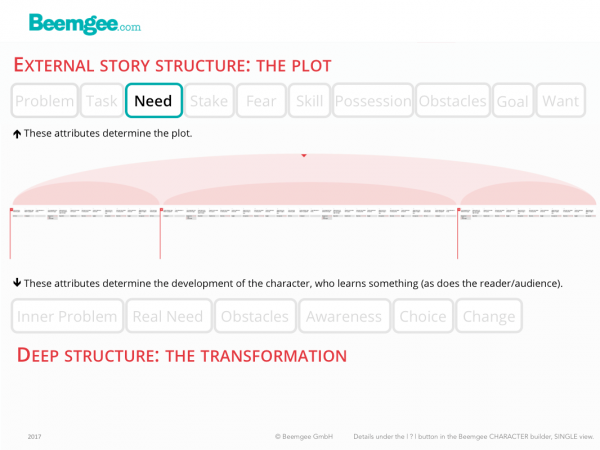

But perhaps the most interesting thing about a character’s want is how it stands in conflict with what that character really needs.

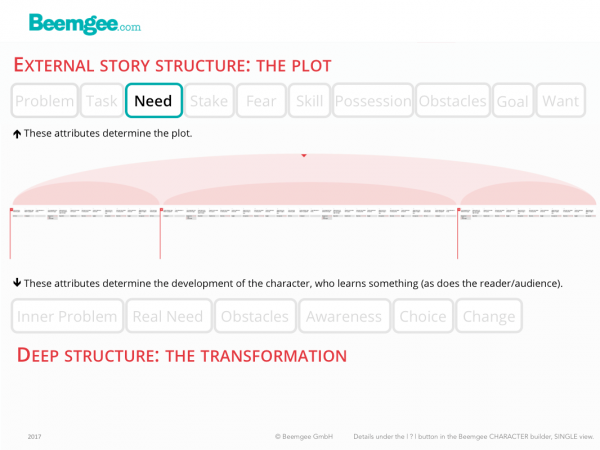

A character with a goal needs to do something in order to reach it.

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the(more…)