What do we mean when we talk about story structure?

A story is a complex entity comprising many interrelating parts. The author imposes some sort of organising principle onto the material, turning the story into a narrative. The result of this forming or shaping of the material is the story structure.

Certain structural markers are so explicit that the audience is aware of them, such as chapters in novels. Elizabethan plays are typically divided into five acts. A film script is broken down into acts, sequences, and scenes.

Beats

But there are structures that are not usually made obvious or explicit. For example, a scene may be broken down into beats – marked only by the moments when the mood or relationship the scene describes changes. Two characters are having a conversation, character A says something which makes character B react in a different way from what A expected – that’s a beat.

The term beat is also sometimes used when marking such changes on a bigger scale, across an entire narrative. Some screenwriters work with so-called beat sheets; in the Beemgee outlining tool, the plot event cards are perfect for creating beat sheets, since each card is designed to stand for one plot event. In a beat sheet, a beat is one unit of plot. If you think of narrative as a chain of events, then each beat is a single link. In one school of thought, a Hollywood movie is ideally constructed of exactly 40 such beats. (more…)

Highlight and Filter (i.e. find) Your Plot Input

(more…)

The process of writing is unique to each author.

There is no right or wrong way to write a work of fiction. Perhaps the main thing is to just sit down and get on with it.

Many authors start by writing the beginning of the story and working their way through to the end. This seems intuitive, as it mirrors the way narratives are normally received – from opening to resolution. Furthermore, it allows a development of the material that feels natural, beginning probably with a setting and a character or two and growing in complexity as the story progresses.

But this isn’t the only way to get a story written. The author is not the recipient, after all. The author is the creator.

Creative habits seem to differ according to medium. Most screenwriters spend a lot of time working out the intricacies of plot and complexities of character before beginning to actually write the screenplay. Some novelists, on the other hand, seem to require the writing process in order to get to grips with the material. For such authors, the act of working on text is so intimately intertwined with the craft of dramaturgy that the shaping of the story has to be performed simultaneously with the writing of it.

Flow

In some cases, a writer might have a fairly clear idea in mind where the story is headed, or already be aware of certain key scenes that ought to be included. In others, the author may not know how the story ends(more…)

Conflict is the lifeblood of story.

In real life, conflict is something we generally want to avoid. Stories, on the other hand, require conflict. This discrepancy is an indicator of the underlying purpose of stories as a kind of training ground, a place where we learn to deal with conflict without having to suffer real-life consequences.

In this post we will look at:

- An Analogy

- Archetypal conflict in stories

- Conflict between characters

- Conflict within a character

- The central conflict

Along with language (in some form or other, be it as text or as the language of a medium, such as film) and meaning (intended by the author or understood by the recipient), characters and plot form the constituent parts of story. It is impossible to create a story that does not include these four components – even if the characters are one-dimensional and the plot has no structure. However, it is formally possible to compose a story with no conflict.

It just won’t be very interesting.

(more…)

In essence, there are three kinds of opposition a character in a work of fiction may have to deal with:

- Character vs. character

- Character vs. nature

- Character vs. society

However, this way of categorising types of opposition is not equivalent to internal, external and antagonistic obstacles. Any of the three kinds of opposition listed above may be internal, external, or antagonistic. It depends on the story structure.

External opposition

In any story, the cast of characters will likely be diverse in such a way as to highlight the differences and conflicts of interests between the individuals. In some cases, certain roles may be expected or necessary parts of the surroundings, i.e. of the story world. In the story of a prisoner, it is implicit that there will be jailors or wardens, whose interest it will be to keep the prisoner in prison, which is in opposition or conflict with the prisoner’s desire for freedom.(more…)

Outlining a story means developing the characters and structuring the plot.

Beemgee will help you outline your plot using the principle of noting ideas for scenes or plot events on index cards and arranging them in a timeline. This is a separate process from actually writing the story. Most accomplished authors outline their stories before writing them, because it saves rewrites later.

In this post we will explain –

The Beemge author tool is divided into three separate areas, PLOT, CHARACTER and STEP OUTLINE. You navigate them easily in the top menu.

Important note: Make sure to stay in the same browser window in whichever area you’re working. Having one project open in multiple windows may result in some of your input being lost.

How To Create An Event Card

(more…)

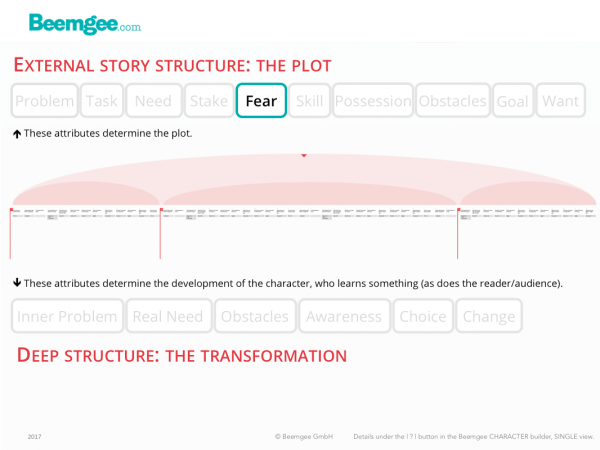

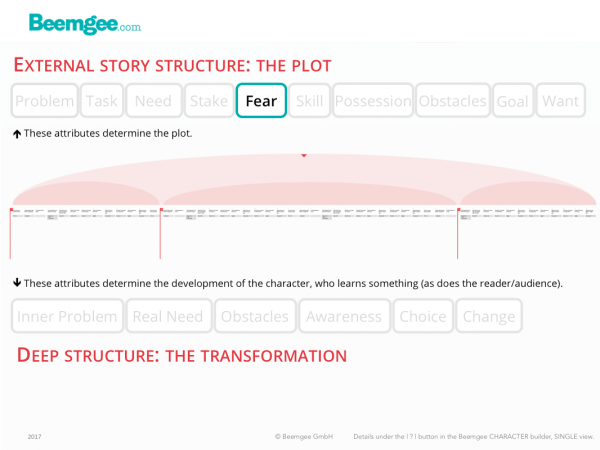

Certain universals are feared by almost everyone. Such as death.

If a character in a story has loved ones, losing them is an even stronger fear.

A story engages the audience or readers more strongly when there is something valuable at stake for the character, such as his or her own life or that of a loved one. So giving a character a universal fear is usually a good place to start.

Giving a character a specific fear to overcome requires this information to be placed early in the narrative. The fear is then faced at a crisis point in the story, usually the midpoint or the climax.

Characters can have specific fears. A fear which is specific to one character must be set(more…)

You’re on a boat, and you see somebody fall into the water. Which of the following two cases would cause you to react with stronger emotion?

- The water is four feet deep and you know that the guy who fell in is a good swimmer

- The water is four feet deep and the person who fell in is a three year old girl who can’t swim

Presumably your emotional reaction would be stronger if the child fell off the boat. Because you know that the child’s life is at stake. The first situation is not life-threatening, the only thing at stake is the dryness of the man’s clothes and his self-esteem.

The degree you care about events that happen to people, and to yourself, is directly related to what’s at stake. This applies as much to fictional characters as in the real world.

Hence it is immensely important for storytellers to(more…)

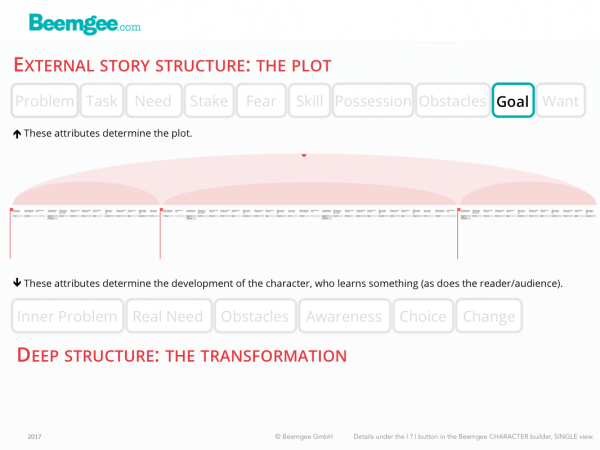

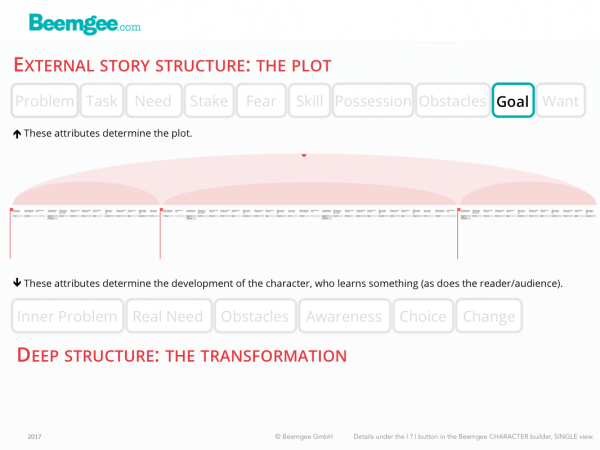

In a story, if the treasure hoard is what the character wants, then slaying the dragon is the goal.

The goal is what the character thinks will lead to the want.

Since the hoard has been there for ages, there must usually be some sort of trigger for the story to get started, i.e. for the character to want the hoard now, at the time the story begins. Often, an external problem creates such a trigger. It might supply a reason why the hero needs the hoard now, something more specific than just the general sense of wanting to be rich. Perhaps the hoard isn’t the reason at all. Perhaps there is a princess in distress, which certainly adds urgency to the matter. Either way, dealing with the dragon is the goal.

If somebody says the word “goal” to you, the image that springs to mind might have to do with the ends of a football pitch. The(more…)

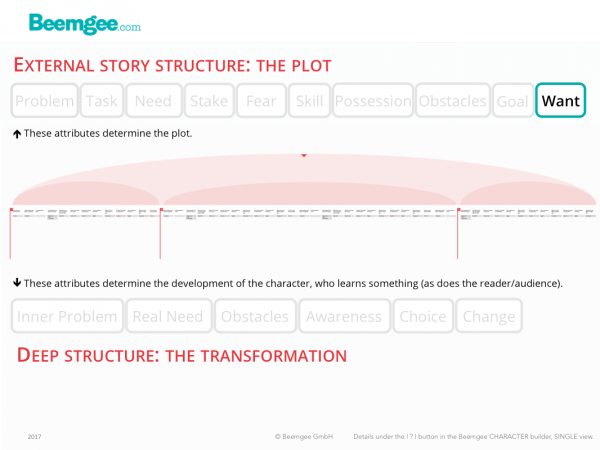

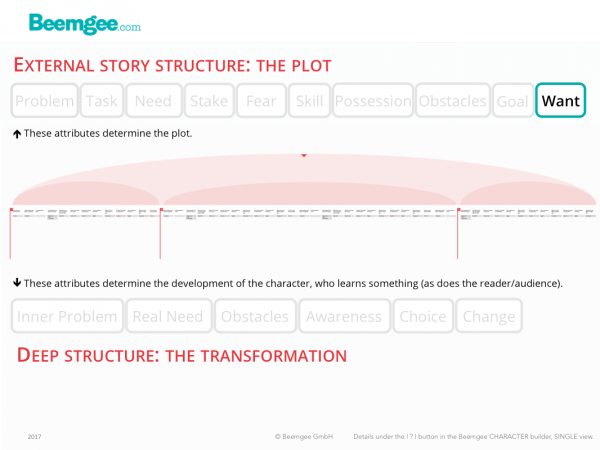

Stories are about people who want something.

We can distinguish between two different types of want:

- the wish, or character want

- the plot want

Marty McFly wishes to be a musician (character want). He also wants to get Back to the Future (plot want).

The wish or character want is a device which adds cohesion to the story, usually in the form of the set-up/pay-off. Marty is seen at the beginning of the film practicing the guitar; at the end of the film he plays at a concert. The wish is a useful technique to make the character clearer to the audience, but it is not essential to composing a story.

More important is what we have called the plot want. As a result of the external problem – the trigger event that sparks the chain of cause and effect which the bulk of the plot consists of –, the character feels an urge, which provides the motivation for the character’s actions in the story.

The want is the state after which the character strives, and is distinct from the goal.

In this post we’ll be talking about active vs. passive characters, motivation, the difference between a want and a goal, a couple of writer traps to avoid, and contradictory wants.

Active Characters

Characters have to be actively acting of their own volition. The want has to be urgent and strong enough for them to do things. If the want is missing or too weak, the character will lack motivation and appear passive. A passive character is usually not interesting enough to hold the audience’ or readers’ attention.

Why is this so?

An evolutionary explanation of stories as practice for problem-solving attempts to shed light on the phenomenon: When characters react to events rather than cause them, they appear weak, like victims. Which means that there is not much we can learn from them. Humans experience stories physically and emotionally (our hearts beat faster, our palms sweat), and since we learn from experience, we instinctively prefer stories which provide us with experiences that benefit us in some way. Which tends to be the case when we experience stories of self-motivated problem-solving.

Motivation

There is a good reason for that cliché about actors always asking about their motivation. It is motivation that prompts the characters in a story to do the things they do. Stories seem to work best not only when characters are active rather than passive, but often when they have comprehensible reasons for their activity.

The reason for what a character wants is usually comprehensible for the audience or reader because of the external problem. In simple terms, the character wants to solve the problem. Take the Cinderella story as an example. Her problem is that she is bound to the stepmother and her two nasty daughters.

In other words, the want is a vision the character has of his or her situation without the problem. Hence what the character wants is actually a particular state of being. Such a state might mean being in a position of wealth, power or respect, or being in a happily ever after relationship. Cinderella wants merely to be free of her involuntary servitude, if only for a little while.

This makes the want distinct from the goal, which is the specific gateway to the wanted state of being, as perceived by the character. A story usually sets up a goal the character needs to reach or attain in order to achieve the want. In Cinderella’s case, it is attending the ball.

So, a story has its characters pursue their wants. These different wants oppose each other, causing conflicts of interest. The conflicting wants make the characters active, and the audience/readers like stories about actions, that is, about characters who do things.

Sounds simple.

And yet frequently stories seem to mess up on this vital point.

Next to passive characters without a strong enough want, lack of clear motivation is a huge writer trap. It is possible to write a whole story full of characters who are reactive instead of active, or who do things of their own volition but without that volition being clearly recognisable to the audience/reader. It is perhaps even tempting to write stories like that, because they seem more lifelike. In real life, people do not necessarily have distinct goals. Often, our wants are vague and not clearly definable. What about writing a realistic story about a character with a general sense of dissatisfaction, who, like so many of us, has lost sight of any clear objective in life?

It’s doable, certainly. But the audience/readers will probably start to look for the specific want of such a character. They would probably begin to expect the story to be about this character’s search for a clear objective in life. That might be the want the audience would tacitly ascribe to the character.

And if the story does not bear such motivation out, the risk is significant. Because stories in which the audience does not understand what the characters want lack emotional impact.

Contradictory Wants

A way of adding psychological depth and emotional complexity to characters is to give them several and even contradictory wants. Gollum in Lord Of The Rings wants the ring. Yet a part of him also wants to give up the ring and help Frodo. Next to solving the case, Marty Hart in True Detective wants to be a good husband and family man, but he also wants affairs with other women. That’s three wants for one character.

Is it really always necessary for every character to have a clearly defined want?

No. Because, of course, there are exceptions. In certain cases, the author might deliberately obfuscate the why of a character’s actions in order to inject mystery. Not knowing something keeps the audience/reader guessing and turning the pages or not switching the channel. Usually this mystery is cleared up at some point. The audience tends to expect that. Which implies that even if the want was not made clear to the audience early in the story, it was there in the character nonetheless – and certainly the author was aware of it.

Injecting mystery in this way is not in itself a writer trap. But nearly. When tempted to use such a device, an author should at least consider if it would not actually be more interesting for the audience to know the character’s motivation.

Having said that, there are rare cases where a character’s motivation does remain unexplained. And those cases can be powerful. Especially when it’s a baddy we don’t understand.

Think of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who is simply bad to the bone and we’ll never really know what made him so. Shakespeare – deliberately, one presumes – gives no hint as to what Iago hopes to achieve by ruining Othello. Shakespeare might easily have given Iago some clearly understandable motivation, such as revenge of a past wrong, envy of Othello’s success, desire to usurp Othello’s position, lust for Desdemona. But he didn’t. And Iago is one of the most superb villains ever.

But perhaps the most interesting thing about a character’s want is how it stands in conflict with what that character really needs.

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

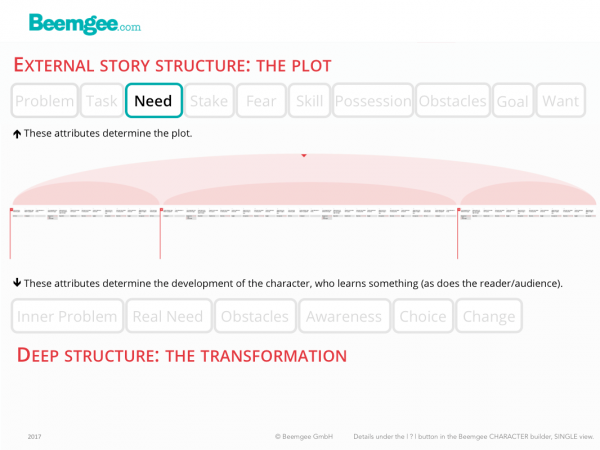

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal: rescue the princess, steal the diamond. In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

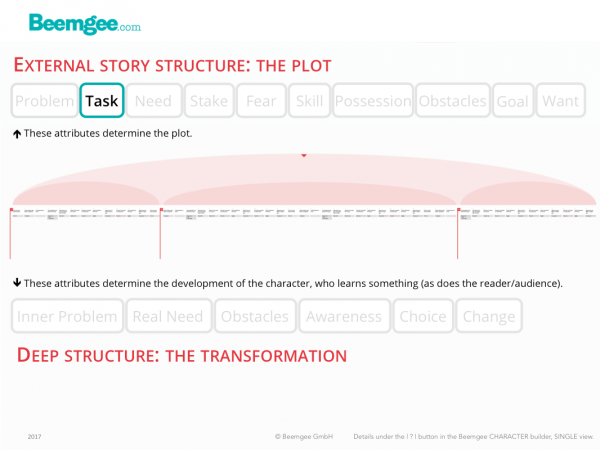

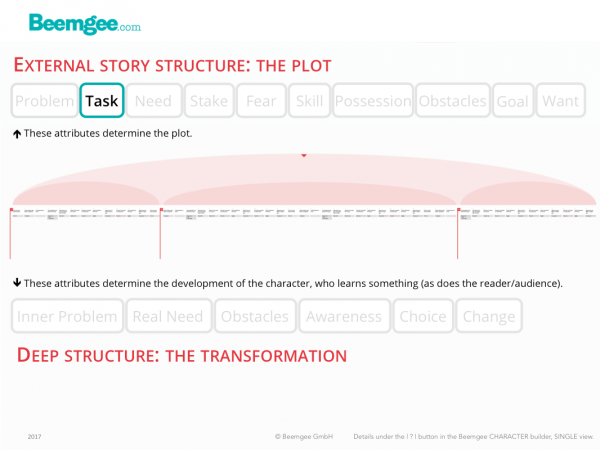

In most stories, the protagonist has something to do.

The task is the more or less explicitly defined mission a character sets out on in order to reach the goal and thereby solve the external problem.

Many of the major characters in a story will have something to do, which may result in them getting in each other’s way.

Task as Function

In a story, more or less everyone has a task. What characters do in a story defines them and determines their roles and narrative functions in the story. In this sense, it is an antagonist’s task to get in the way of the protagonist; an ally’s task is to help the protagonist; a mentor’s task is to advise the protagonist and set them on their way.

But while all that is true, it isn’t really what we mean by task.

Task as Action

The characters’ actions make them who they are. To define a character’s task is to state clearly what that character has to achieve in the story. It is the action that leads to(more…)

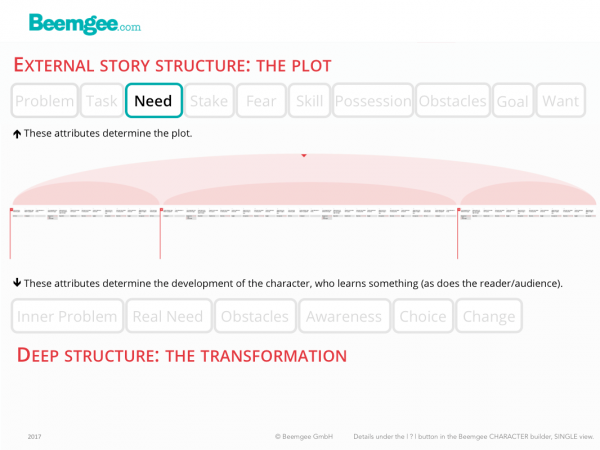

A character with a goal needs to do something in order to reach it.

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the(more…)

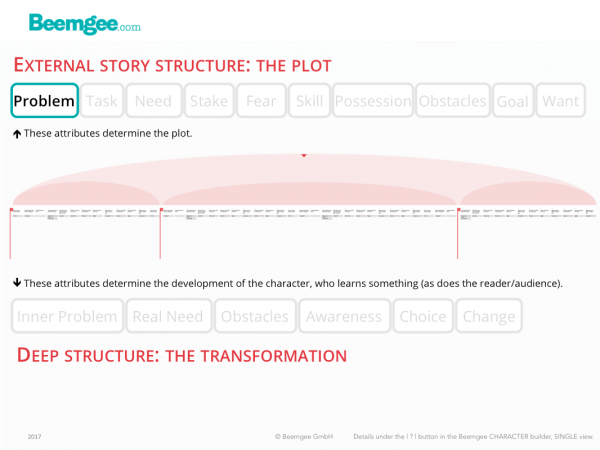

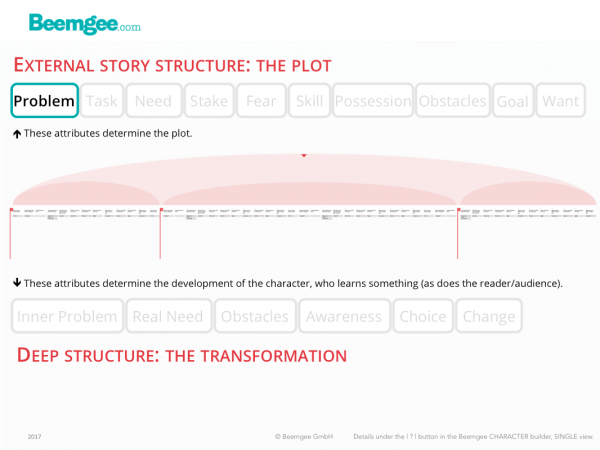

In stories, characters solve problems. This is the basic principle of story.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes. What’s more, in storytelling they come from within and without. The problems that come from within are hidden, internal, and it is quite possible for a character not to be aware of them. They are typically character flaws or shortcomings.

But they are not usually what gets the story going. Most stories begin with the protagonist being confronted with an external problem.

The external problem of the main character triggers the plot. It is shown to the audience as the incident which eventually incites the protagonist to action.

In some genres this is easy to see. In crime or mystery fiction, the external problem is almost by definition the crime or mystery that the protagonist has to deal with.(more…)