The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

The protagonist is the main character or hero of the story.

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. And for simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

- Is the protagonist the most interesting character in the story?

- What are the most important aspects of the protagonist for the author to convey?

- What about the transformation or learning curve?

How interesting must the protagonist be?

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

(more…)

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal: rescue the princess, steal the diamond. In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

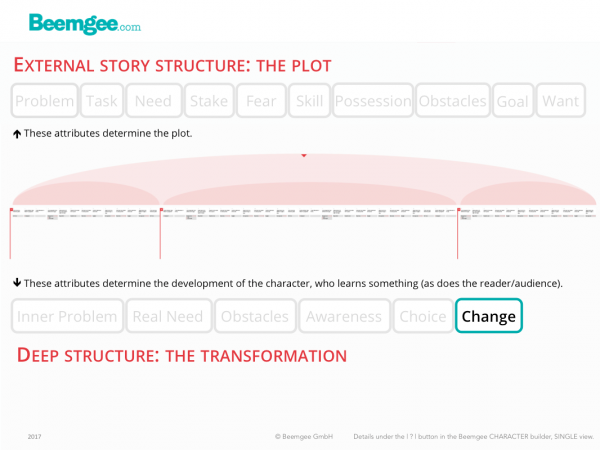

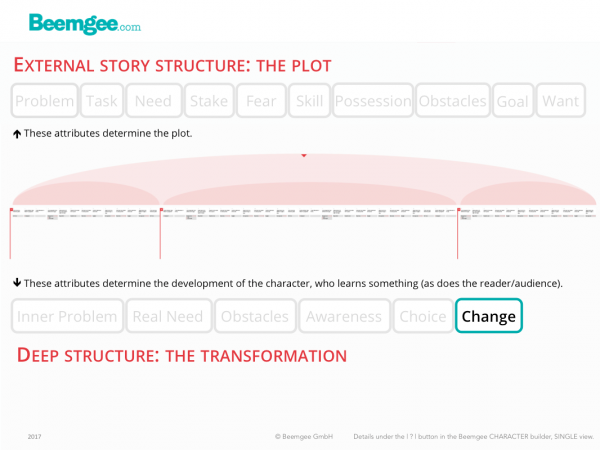

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning. But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

So within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

(more…)

Archetypes in stories express patterns.

While plots may be “archetypal” when they exhibit certain forms, in this post we are concerned with character archetypes.

In modern storytelling, to consider them as archetypes might suggest a bit of a corset, perhaps even a straightjacket for the characters. For today’s author, to present a character as an archetype does not seem conducive to achieving psychological verisimilitude.

But an archetype is not the same as a stereotype. An advisor or mentor does not need to be a wise old man like Obi-Wan Kenobi. And an antagonist does not need to be a baddy.

Consider archetypes as powers within a story. Like planets in a solar system, they have gravity and they therefore exert force as they move.

Archetypes denote certain general roles or functions for characters within the system of the story. There is ample room for variation within each role or function. Boundaries between one archetype and another may be fuzzy. And it is possible for one character to stand for more than one archetype.

Archetypes Through The Ages

(more…)

More than any other part of a story, the beginning has to grab the audience’ or reader’s attention.

In the beginning, before audience or readers are emotionally involved and concerned about the fates of the characters, the danger of them turning away from the story is greatest.

Now, there’s more to a beginning than the kick-off event. While being an attention grabber, the entire first section of a story also has to establish the following:

- Who the story is about

- What the story is about

- Where the story takes place

That sounds self-evident, but all the elements needed to answer those three points amount to an awful lot of information. And at this stage, the audience or readers are not yet patient or forgiving, because they are not yet emotionally hooked.

In this post we will:

- look at the who/what/where

- determine the two key events that the first section of a story must include

- provide a checklist of all the elements the first part of a story requires

Who/what/where

(more…)

Stories are about people. Even the ones about robots, or rabbits, or whatever.

If you’re thinking about composing a story, you will probably have some characters in mind that will be performing the action of the story. In stories, action and actors (in the sense of someone who does something) are pretty much the same thing looked at from two differing perspectives, as we have noted in our post Plot vs. Character.

What sets characters in fiction apart from people in life is that characters tend to fulfil narrative functions in their story. People, on the other hand, live their lives by acting naturally according to the dictates of their personality. A story is a more or less enclosed unity, while an individual’s life is part of a greater whole. Only in retrospect do we sometimes overlay a narrative onto the biography of an individual – because we tend to feel happier when we perceive structure or direction in the lives of others or indeed our own. We can extract more meaning out of a life that can be told with structure and direction. In fact, there is no way of recounting a person’s biography without making choices concerning structure. If we’re honest, even the choice of which events to relate and how to relate them injects a fair amount of fiction into the story of a life, especially when that life is our own as we tell it to others or ourselves.

Many stories focus primarily on one protagonist. In fiction at least, the protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. The(more…)