Author and creative writing teacher Jesse Falzoi was born in Hamburg and raised in Lübeck, Germany. Back in the nineties, after stays in the USA and France, she moved to Berlin, where she still lives with her three children.

She has translated Donald Barthelme stories into German. Her own stories have appeared in American, Russian, Indian, German, Swiss, Irish, British and Canadian magazines and anthologies. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College.

Her new book on Creative Writing is released end of May 2017.

At the age of twenty-one I quit university and bought a one-way ticket to San Francisco, USA. I wanted to get far away from my first attempts to grow up. I wanted to get away from a frustrating relationship and boring courses and everything that was pushing me to take life more seriously. I didn’t have any plans what I would be doing in San Francisco but I had the address of an acquaintance I had made a year before. I went on a journey that was physical in the beginning and became more and more spiritual during the process. I bought a return ticket in the end and went back to my hometown just to pack my suitcases for good; I’d be staying in Germany, but I wouldn’t be staying home.

(more…)

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the(more…)

The protagonist is the main character or hero of the story.

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. And for simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

- Is the protagonist the most interesting character in the story?

- What are the most important aspects of the protagonist for the author to convey?

- What about the transformation or learning curve?

How interesting must the protagonist be?

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

(more…)

In stories, characters are faced with obstacles.

These obstacles come in various forms and degrees of magnitude. And they may have different dimensions: they may be internal, external, or antagonistic.

Often the obstacles that resound most with a significant proportion of the audience are the ones that force the main characters to face and deal with problems within themselves, in their nature. In other words, with their internal problem.

Internal obstacles are the symptoms of the characters’ flaws, of the internal problem. The audience perceives them as scenes in which the character’s flaw prevents her progress.

Not every story features characters with internal problems. An internal problem is not strictly speaking necessary in order to create an exciting story.

But it helps.

The Emotional Truth

An internal problem makes the character appear fallible – and thus more credible, more human, more like us. Internal problems are invariably emotional and private. They express(more…)

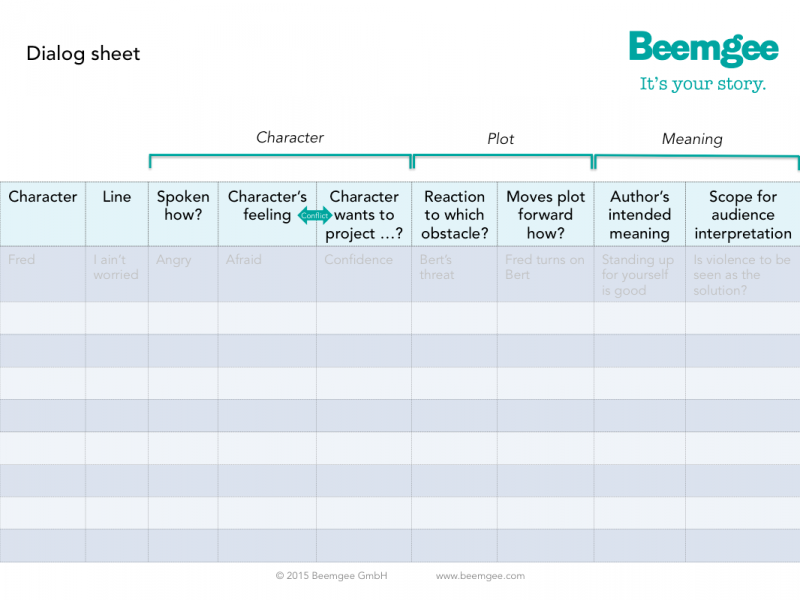

Dialog enlivens stories. But writing dialog well is really hard.

For a start, there is the rule of thumb that it’s better for the author to use action to explain things or move the plot forward than dialog. When the author makes characters say things solely to convey some bit of knowledge to the audience or reader, the lines tend to feel false.

Nonetheless, Elmore Leonard noted how readers don’t usually skip dialog. People like dialog. Dialog can be exciting. So authors had better not avoid it altogether either.

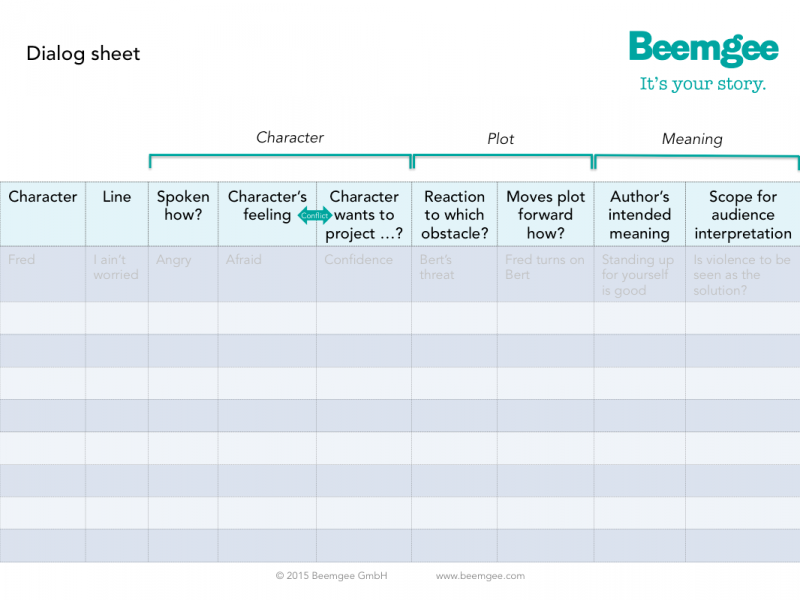

As an author, here are the seven things you ought to consider about every single line of dialog you put into your characters’ mouths. We’ve created this free table to help you. Feel free to download, use and share it.

1

If you’re writing(more…)

You’re on a boat, and you see somebody fall into the water. Which of the following two cases would cause you to react with stronger emotion?

- The water is four feet deep and you know that the guy who fell in is a good swimmer

- The water is four feet deep and the person who fell in is a three year old girl who can’t swim

Presumably your emotional reaction would be stronger if the child fell off the boat. Because you know that the child’s life is at stake. The first situation is not life-threatening, the only thing at stake is the dryness of the man’s clothes and his self-esteem.

The degree you care about events that happen to people, and to yourself, is directly related to what’s at stake. This applies as much to fictional characters as in the real world.

Hence it is immensely important for storytellers to(more…)

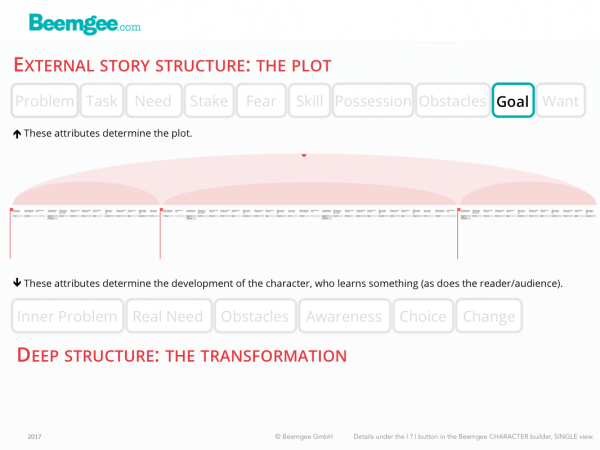

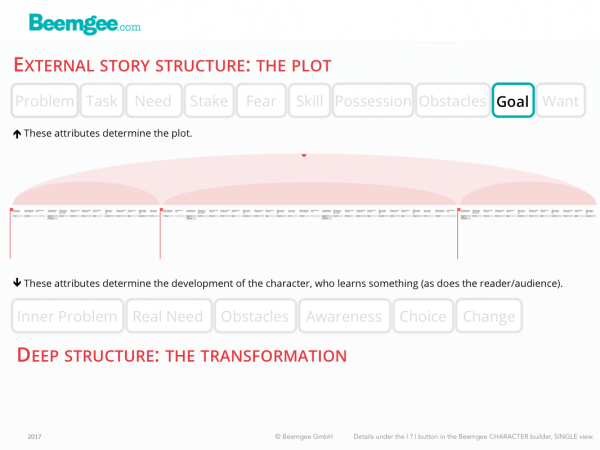

In a story, if the treasure hoard is what the character wants, then slaying the dragon is the goal.

The goal is what the character thinks will lead to the want.

Since the hoard has been there for ages, there must usually be some sort of trigger for the story to get started, i.e. for the character to want the hoard now, at the time the story begins. Often, an external problem creates such a trigger. It might supply a reason why the hero needs the hoard now, something more specific than just the general sense of wanting to be rich. Perhaps the hoard isn’t the reason at all. Perhaps there is a princess in distress, which certainly adds urgency to the matter. Either way, dealing with the dragon is the goal.

If somebody says the word “goal” to you, the image that springs to mind might have to do with the ends of a football pitch. The(more…)

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal: rescue the princess, steal the diamond. In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

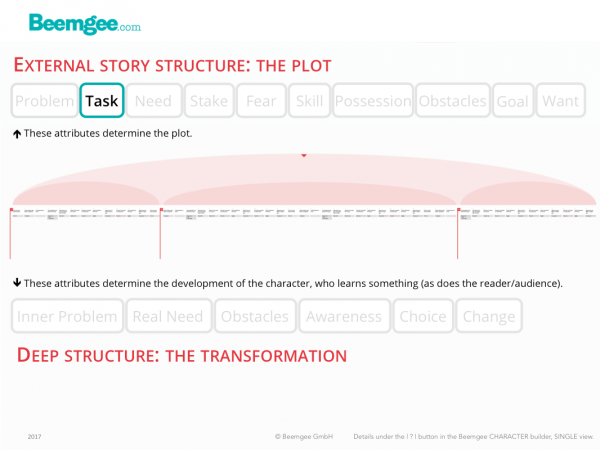

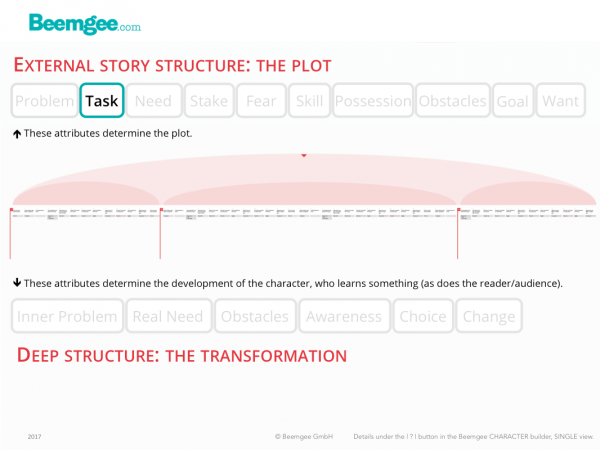

In most stories, the protagonist has something to do.

The task is the more or less explicitly defined mission a character sets out on in order to reach the goal and thereby solve the external problem.

Many of the major characters in a story will have something to do, which may result in them getting in each other’s way.

Task as Function

In a story, more or less everyone has a task. What characters do in a story defines them and determines their roles and narrative functions in the story. In this sense, it is an antagonist’s task to get in the way of the protagonist; an ally’s task is to help the protagonist; a mentor’s task is to advise the protagonist and set them on their way.

But while all that is true, it isn’t really what we mean by task.

Task as Action

The characters’ actions make them who they are. To define a character’s task is to state clearly what that character has to achieve in the story. It is the action that leads to(more…)

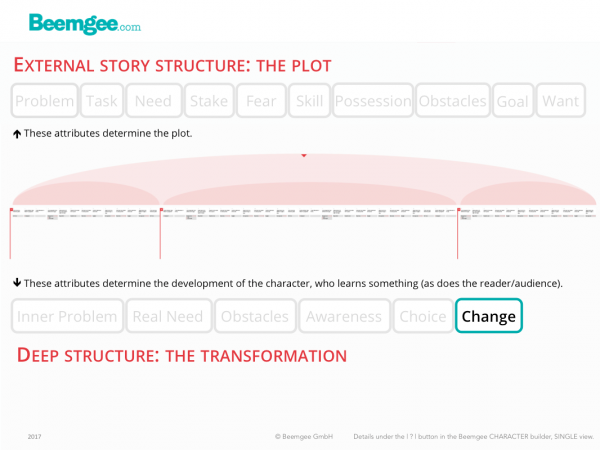

If there is one thing that ALL stories have in common, it is change.

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning. But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

So within a story, what changes?

At the very least,

- one of the characters, usually the protagonist

- often other characters too

- sometimes the whole story-world

(more…)

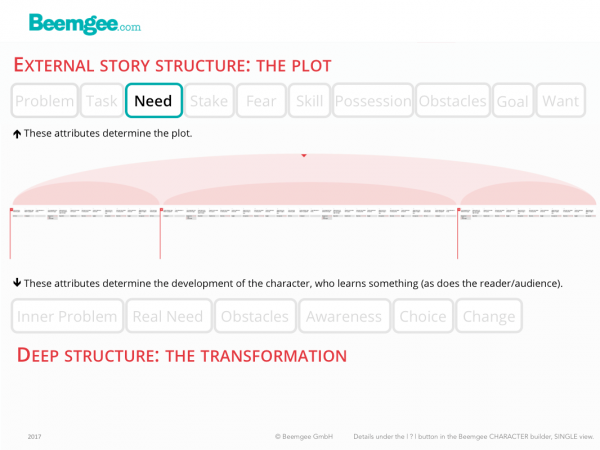

A character with a goal needs to do something in order to reach it.

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the(more…)

What’s the problem? Does the character know?

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

- A character’s awareness of his or her own internal problem or motivation

- A difference between one character’s knowledge of what’s going on and another’s

- The narrator knows more about what is going on than the character

- The audience/reader knows more than the character – dramatic irony

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

- Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation

- The Story Journey – and where to place the revelation

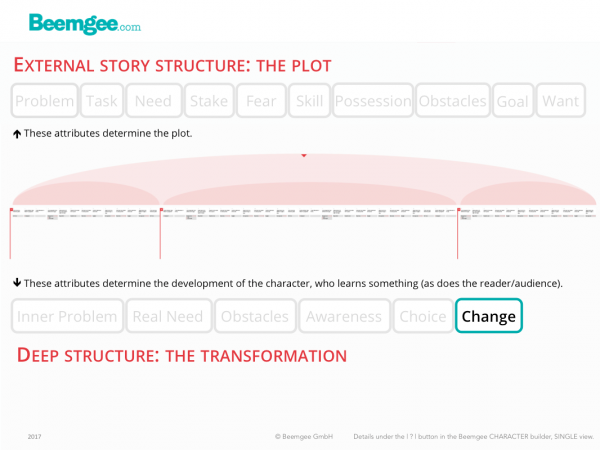

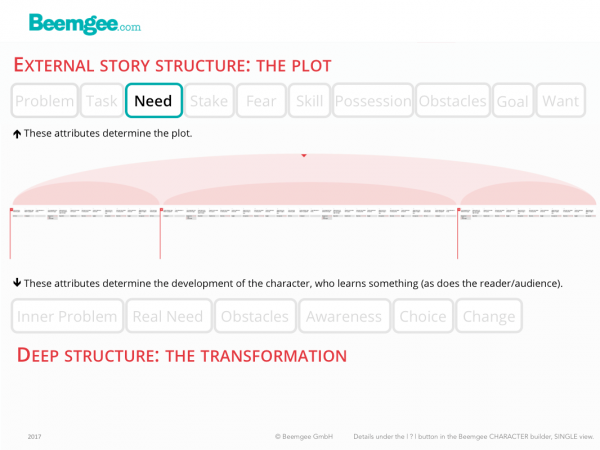

- Surface Structure and Deep Structure

- The Need for Awareness – or, Alternatives to Revelation

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation (more…)